How Can I Know if a Book is Living?

Originally Published for The Old Schoolhouse Magazine, 2012

It cherishes you; that’s how. Enough said. Article done . . .

Really, that’s all we need to know! But a terrible thought assails my mind . . . What if you have never been cherished by a book? What if you have never felt a living book’s respect for your position as the son or daughter of the Lord God, High King?

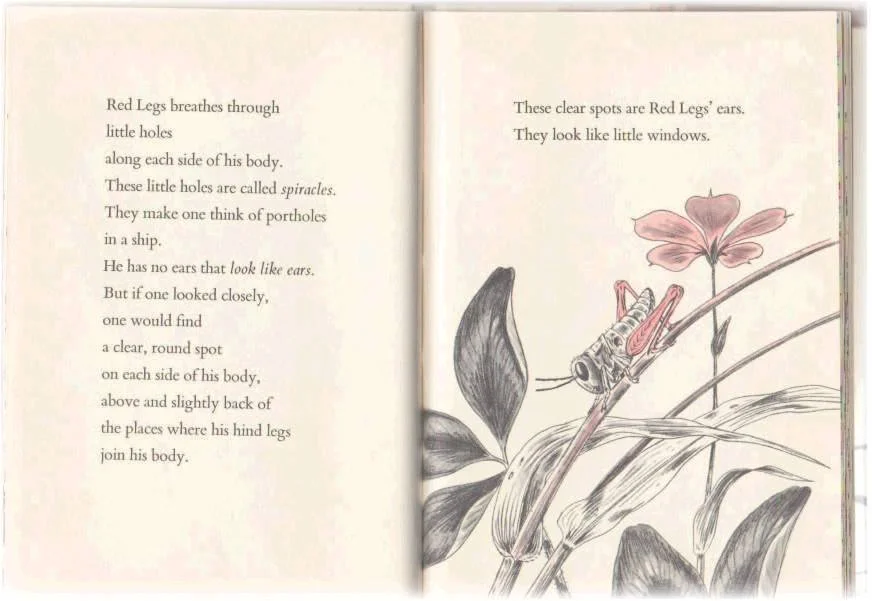

ABOVE: Red Legs by Alice Goudey (New York: Scribner’s, 1966)

Believe it or not, just typing those words makes me cry.

I grieve, grieve, grieve, grieve, grieve that most modern children have never felt honor from a real book, a worthy book!

Back in my day (I am 51, going on 206), virtually all youth books were living. You could literally feel it. The paper itself was luxurious, creamy, and supple.1 The illustrations were lovingly hand-drawn or painted by superb talents. The fonts were dignified. The generous “white space” surrounding the text on each page gave the eye a lovely rest and admiringly framed the words themselves. Even the breathing room between the lines, in books for young readers, was charitable. When you picked up the book—always done with a respect mutual to that received from the book—there was a pleasing heft, for everyone from the publisher to the culture at large to the parent to the child who would take the book to bed (for secret reading under the sheets by flashlight) cared about this precious gift of civilization. The most significant quality, though, was its way of speaking to readers, which was strikingly different than today’s!

But, something was profoundly different then, back in the “Golden Age of Children’s Literature” (mid-1930s to 1970). This difference is so large that it is almost hard to see. On the other hand, it is also so potent that we can’t help witnessing its effects every day, and anything that changes the entire society changes its children’s literature too.

You see, absolutely everything hinges on what I call the Big 2 Beliefs: (1) What does a society believe to be true about God and (2) What, then, do they believe to be true about mankind? You may think we’ve wandered to the hinterlands of philosophy here, but we haven’t. Because, when the United States was a land steeped in Judeo-Christian beliefs, everything was so different! Even children’s books! But, of course . . . because:

• When there was a basic respect for God as Creator, then humans, His creation and the apple of His eye, were also respected. The books set before them should be worthy! They “looked” up to humans, wanting to serve them with the best writing, instead of speaking down to them.

“They capture the issues of life in such a way that they challenge the intellect, they inspire the emotions, and they arouse something noble in the heart of the reader.” —C. S. Lewis

• When there was a basic admission of God’s presence, then the world was seen as primarily spiritual, not material; thus, human beings were spiritual creatures of eternal destiny! The books made for them inspired the soul not merely informed the brain.

• When there was a basic admission that the Bible was the Word of God and that Jesus spoke powerful truth in His story-parables, the same method was used in children’s books—engaging yet revealing narrative, not dry dissertation. Thus, they were riveting stories: masterpieces of biography, historical fiction (exposing real events through composed characters experiencing the action), “un-put-downable” narrative history, geography, science, math, etc., which imparted worthy lessons to the heart and inspired goodness. Yes, even in math (think, String, Straightedge & Shadow, by Julia Diggins, the story of geometry) and science (Physics Can Be Fun, by Wilhelm Westphal or The Romance of Chemistry, by Keith Irwin), the titles say it all!

But then, C. S. Lewis knew this, saying that living books “are just as interesting at 10 as at 50 . . . . They capture the issues of life in such a way that they challenge the intellect, they inspire the emotions, and they arouse something noble in the heart of the reader.”2

Heart, heart, heart. We keep using that word. Isn’t that what we long to feed, mature, and mold in a child when we homeschool? Then we must seek materials that speak to the heart! This takes a bit of doing in a culture that has rejected Creator-God and instead claims that non-spiritual, impersonal, bioelectrical processes shaped the world and us. Thus, its children’s books mechanically “download” information to the child’s bioelectrical brain rather than nurturing his spiritual heart. Furthermore, since no greater God will be admitted, none of His bigger-than-our-brain ideas will be admitted. All information must become human-sized, chopped up by the educational elite until small enough to fit into the human cerebrum. Thus, you have the murdered factoid, a “byte” of data that the helpless reader (a.k.a. spiritless, mutated, biochemical “factoid receptacle”) should gratefully accept in his pursuit to “adapt” toward “survival of the fittest.” Ah . . . a post-Darwinian children’s book.

Such is the nature of almost every volume on public library shelves, for as the culture goes, so go children’s books. Without God’s heart, there can be no human heart. Without God’s great story, there can be no sub-stories. Without a cohesive Universe Maker, no book can be cohesive. It must instead be fragmented by countless sidebars (hoping to cover the lack of engaging story) or completely separate two-page spreads studded with huge visuals (likewise hoping to swap story-interest for eye-interest) surrounded by dismembered, floating factoids—impersonal and forgettable because they are isolated and heartless. Since the Bible says that the “heart” is the seat of learning (it never mentions the brain once, a theme in Ruth Beechick’s A Biblical Psychology of Learning), we needn’t wonder why little of what we learned in our lab-created textbooks inspired us or stuck with us for life.

Just remember, a great story—like the “greatest story ever told,” as the Bible is often called—needs no artificial inducements. The worthy content does all the attracting and teaching, and it does this so effectively that there are no sidebars, no photo splashes in the middle of each page (to trick the reader into interest), and no questions at the end of the chapter to force retention when the content failed to do so. Ah, such a living book reproduces itself in others! Now we’re talking learning and lifelong impact!

Really, is it necessary for people to reinvent the book? Must we “human-ize” it, when He has already done the most crucial Book perfectly? It makes no more sense than asking a team of scientists to duplicate the countless molecular compounds crucial for human health, reassembling them in a “carrier” that will be simultaneously palatable, digestible, transportable, and marketable, when we could just give our kids a God-made banana, which is all of the above!

We may chuckle, but we must ask: What is it with us? We proud humans keep trying to “improve” on God’s work. But we—who cannot create life—are left to merely dissect what is already alive. In our effort to remake, we fractionalize, blenderize, scrutinize, and geneticize matter into human-sized fragments, which we then reassemble into impressively named amalgams. Now, the selling begins. But none measures up to the Original. Our copies, our factoid-texts, are sallow second-bests. One has only to compare freshly squeezed fruit juice with “powdered drink mix.” I rest my case!

That is why you needn’t worry about spotting a living book! If you can tell the difference between just-off-the-tree orange juice and Kool-Aid, if you can tell the difference between God’s night sky and Van Gogh’s painting of it, if you can tell the difference between Niagara Falls and the rock-tickling trickle at the back of your neighbor’s pond . . . then you can tell the difference between a living book and a laboratory book. You can sniff out the “work of literary art” inspiringly created by a passionate author deeply invested in his field—and not be fooled by publishing mills churning out endless pulp on cheap paper in cramped, creaky-glued bindings and penned by employees punching a clock while writing about oodles of topics. You can tell when a book honors your spiritual essence by embedding the truth (whether it be history, math, science, or any topic), as God did, in story, rather than condescendingly emitting sterile “factoids.” You really can tell! Just be a wise discerner, not a passive consumer! Seek out the treasures, now more readily available than ever thanks to the work of dealers, re-printers, and online publishers in the last twenty years. They are worth having, worth teaching, and worth passing on to your grandchildren. But if there is any last lingering question, let this decide for you . . .

. . . Anything that changes the entire society changes its children’s literature too.

Michelle Howard

Endnotes:

1. The only exception to this throughout the “Golden Age of Children’s Literature” was dur- ing World War II rationing, understandably.

2. Quoted in For the Children’s Sake, by Susan Schaeffer Macaulay (Crossway Books, 1984).

Where Shall I Start?

Michelle’s favorite resources for locating living books:

• Books Children Love by Elizabeth Wilson (widespread availability)

• Who Should We Then Read?, Volumes 1 and 2 by Jan Bloom (www.booksbloom.com)

Michelle’s favorite, little-known living books:

• Books by Stephen Meader and Merritt Parmelee Allen (American history)

• Star and the Sword by Pam Melnikoff (Middle Ages)

• Song of Eve by June Strong (Old Testament history)

• Winston Adventure Books series, multiple authors and periods

• We Were There series, multiple authors and periods

• Garrard Discovery biography series, multiple authors and periods

• Young Sioux Warrior by Frances Kroll (Sioux Indians)

• Sandy and the Indians by Margaret Friskey (Black Hawk War)

• Young Pony Express Rider by Charles Coombs (Wild West)

• Dan Frontier series by William Hurley (Daniel Boone)

• Silence Over Dunkerque by John Tunis (World War II)

• Comanche and His Captain by A. M. Anderson, and others in vintage American Adventure series (Custer’s Last Stand)

• The Gammage Cup by Carol Kendall (Fiction, but about true nation issues)

• Bullwhip Griffin by Sid Fleischman (California Gold Rush)

• Snow Treasure by Marie McSwigan (World War II)

• Detectives in Togas by Henry Winterfeld (Ancient Rome)

• Gift of the Golden Cup by Isabelle Lawrence (Ancient Rome)

• Molly Bannaky by Alice McGill (Colonial)

• The Spy and General Washington by William Wise (American Revolution)

• Boston Bells by Elizabeth Coatsworth (War of 1812)

• Star-Spangled Banner by Neil Swanson (War of 1812)

• Viking Adventure by Clyde Robert Bulla (Vikings)

• The Sword in the Tree by Clyde Robert Bulla (Middle Ages)

• Children of the Covered Wagon by Mary Jane Carr (Oregon Trail)

• Sarah Whitcher’s Story by Elizabeth Yates (U.S. Early Federal Era)

• The Good Ship Red Lily by Constance Savery (Puritans in England)

• Two Travelers by Christopher Manson (Early Middle Ages, Charlemagne)